IKIGAI - Reason For Being

It is common at some point in time across the individual lifespan to question one’s sense of meaning and purpose; one’s reason for existence. Hector Garcia and Francesc Miralles in their book, “Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life,” explore the concept and its embodiment in a long and happy life.

What is your reason for being?

Garcia and Miralles’ research indicates that the Japanese believe we all have an ikigai (i.e., a reason for being; the reason we get up each day; a why; a sense of purpose) and that we carry it within us.

It is not always immediately apparent and does require introspection, reflection and searching. Questions to ask when trying to discover ikigai include:

“what makes me enjoy doing something so much that I forget about whatever worries I might have while I do it?

When am I happiest?[i]

What fills my soul with joy?

What am I truly passionate about?

What is the task waiting for me?

“What does life expect of me?”[ii]

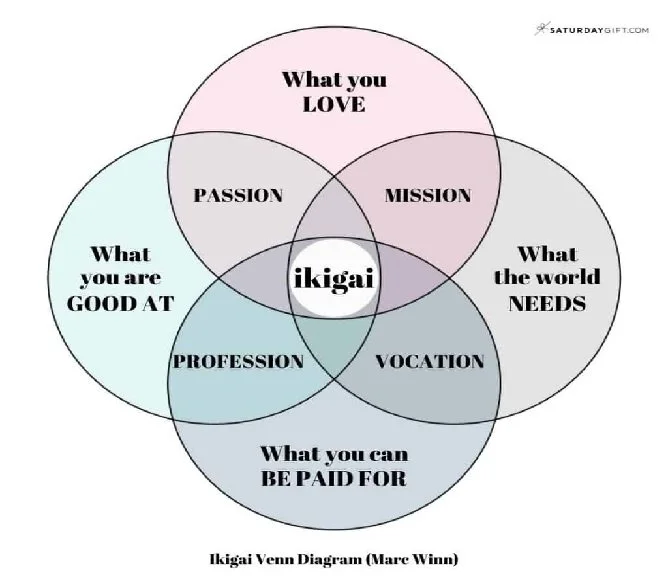

Marc Winn has created a Venn Diagram that demonstrates the interconnecting factors involved in Ikigai:

When you discover your ikigai, pursue it and nurture it, your life takes on a sense of purpose and you’ll achieve “a happy state of flow in all you do.”[iii]

What is Flow?

Csikzentmihalyi defined flow as a state “characterised by merging of action and awareness, complete concentration, strong sense of control, loss of self-consciousness, distortion of time perception, and autotelic (intrinsically rewarding) experience.”[iv] This state is facilitated where there is a balance between clear and proximal goals, perceived skills and challenges and immediate and unambiguous feedback.[v]

Flow conducive activities include leisure activities and work. Consequently, Seligman refers to flow as engagement which is one of the pillars of PERMA (i.e. Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationship, Meaning/Mattering and Achievement).[vi] He asserts that there “are no shortcuts to flow” and that you “go into flow when your highest strengths are deployed to meet the challenges that come your way” – for example, social intelligence, courage, kindness, humour.[vii]

Flow experiences are said to act as an internal “psychic compass” orienting us towards those activities we wish to pursue.[viii] It has also been proposed that flow is not only a vehicle for development but also a component of the good life and life satisfaction and thus an individual’s ikigai.[ix] This is seen in the Takumis (artisans) in Japan. A particular example being the manual skill required to create turntable needles. Takumis like Otakus (fans of anime and manga), inventors and engineers seek to flow with their ikigai. This phenomenon is not limited to Japan but is observed around the world.[x]

Flow allows for optimal experience which requires that we select activities that will bring us into a state of flow and discard or minimise those that simply provide instant gratification (e.g., substance abuse, overeating) or act as a distraction.[xi] To flow, we are required to be absorbed; focused on the task at hand.[xii]

Research highlights that although flow can be present across the lifespan, younger and middle aged adults are more likely to experience it in study or work domains. Whilst older adults more often experience it in leisure.[xiii] So, the vehicles that facilitate flow may change across the lifespan.

Garcia and Miralles suggest the following exercise as a way of trying to identify your ikigai via flow:

Write down all the activities in your life that generate flow

What do these activities have in common?

Why do you think they generate flow for you?

Have you found you generate flow more with intellectual pursuits or when you use your body?

If answering these questions still doesn’t identify your ikigai, they recommend continuing the search and engaging your curiosity to try new things as well as spending more time on the activities that already produce flow.[xiv] Flow “is like a muscle: the more you train it, the more you will flow and the closer you will be to your ikigai.”[xv]

Some of the Rules of Ikigai

The following are some of the key components of ikigia:

1. Stay Active; Don’t Retire

In studying the Blue Zones (i.e., Okinawa, Japan; Sardinia, Italy; Loma Linda, California; The Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica and Ikaria, Greece) and in particular Okinawa, Japan, Garcia and Miralles found that many Japanese people do not technically retire. They continue doing what they love for as long as their health allows. Their connection to their purpose provides value and sustains life.

For example, artists who still create instead of “retiring” are in touch with their ikigai which can bring happiness and purpose into their life e.g., Carmen Herrera was 100 yrs of age at the time Garcia and Miralles wrote their book and is reported to have sold her first canvas at age 89 yrs and has works hanging in the Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art.[xvi]

2. Take it Slow and be Mindful

Pursuing your ikigai does not require rush. To achieve a better quality of life, it is important to slow down.[xvii] When we slow down, we become more present and develop greater self-awareness and mindfulness.

Mindfulness originates from Buddhist traditions and involves present moment by moment awareness without judgement of ones surrounding environment (e.g., sights, sounds, smells), feelings, thoughts and bodily sensations. Houlder and Houlder (2002)[xviii] believe “that when you are mindful you are highly concentrated, focused on what you are doing, and you are collected -poised and calm with a composure that comes from being aware of yourself and the world around you as well as being aware of your purpose.”

Mindfulness is the opposite of operating on automatic pilot e.g., getting from A to B without realising how you did that such as when you are walking or driving a car along a familiar and repetitive route.

The more aware you are of your thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations the greater your potential is to emotionally regulate and choose how you respond and react to events and situations – you do not need to revert to old unhelpful thinking styles and behaviour patterns. You can intentionally shift your attention to the present without worrying about the past or the future.[xix]

Engaging in mindful based activities such as:

mindful breathing (i.e., focus “on the sensation of your breath as it enters and leaves your body. Pay attention to the rise and fall of your abdomen or the feeling of air passing through your nostrils”[xx])

·mindful journalling (i.e., set aside a time and an appropriate space to write down your emotions, thoughts and experiences. This can assist emotional processing and self-reflection)

mindful walking (i.e., whilst you are walking, concentrate on the feel of the ground under your feet and your breathing. Just observe what is around you as you walk, staying IN THE PRESENT. Let your other thoughts go, just look at the sky, the view, the other walkers; feel the wind, the temperature on your skin; enjoy the moment); and

mindful eating (i.e., slow down and savour the sensory experience, notice textures colours, smells and flavours. Chew slowly)

has a positive impact on mental health and well-being[xxi].

Research has shown that mindfulness can reduce stress and anxious and depressive symptomology, improve psychological well-being and cognitive functioning and increase positive affect and life satisfaction amongst other benefits.[xxii]

3. Follow the 80% Secret to Eating

Stop eating when you start to feel full.[xxiii] The idea is to eat less than your hunger demands.[xxiv]

4. Exercise and Reconnect with Nature

The WHO defines mental health as a “state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well and contribute to their communities. It has intrinsic and instrumental value and is integral to our well-being.”[xxv]

A core component of mental health and well-being is exercise. It “enhances quality of life, alleviates psychiatric and social disability and reduces depressive symptoms.”[xxvi] It also has the potential to improve sleep, increase bone and muscle strength, cardiovascular health and generate improved self-esteem.[xxvii]

Dr Elissa Epel notes that when we shift our physical environment we change our mental state.[xxviii] The type of environment however can play a role. Research into indoor vs outdoor activities has shown that activities that occur outdoors, aka “green exercise” are more restorative.[xxix] Epel notes that when we move into the natural world, our “mind moves from conditioned thought patterns – rapid thoughts, negative self-talk, anticipating what’s next – to discursive thought which is slower, calmer, creative, curious.”[xxx]

When we immerse ourselves in nature, be it in a green or blue space; when we pay attention to the susurrus of the trees, birdsong or the sound of water, the negative distractions of daily life like technology and social media aren’t there. Instead, we immerse ourselves in “a sanctuary environment that calms the mind and eases the body.”[xxxi] This is known as the “attentional restoration effect”.[xxxii] The opposite, however, can be true for urban environments, which can trigger heightened alertness, vigilance[xxxiii] and social isolation.

Not only do we usually experience the attentional restoration effect but when we are participating in green exercise such as walking, hiking, horse-riding, running or bike riding for example, we tend to do these activities for longer and at higher intensities than if we were doing indoor activities.[xxxiv] An explanation for this may be reduced perception of effort and reduced internal fatigue.[xxxv]

Because the impact of natural spaces is so high, construction of green networks and eco-garden cities is important and has been long recognised by landscape architecture, urban design, civil engineering and architectural disciplines.[xxxvi] Research has noted that when the attractiveness and spatial scale of parks is high, a natural flow between parks occurs and we engage with the “people to nature” process of visiting ecosystem services.[xxxvii]

Good architecture also acknowledges the association between reducing stress and depression and increased cognitive functioning, concentration, job satisfaction and well-being with views of nature, access to natural light and fresh air and seeks to connect with the outside via indoor and outdoor planting schemes as well as utilisation of natural materials.[xxxviii]

If one lives where it might be difficult to move into a natural space daily, turning to exercises such as Tai Chi, Yoga or Qigong for example can be helpful in creating mental and physical alignment and shielding against stress.[xxxix] Research into the Blue Zones also suggests that the key is movement as opposed to intensity. For example, in Ogimi in Japan the daily routines of people over 80 and 90 yrs of age were characterised by constant movement. They would get up early, go for a walk, weed their gardens, play games with their neighbours and so forth. Movement coupled with an awareness of the breath are two key components of aligning consciousness with the body and thus reducing stress and aiding access to ikigai.[xl]

5. Cultivate Deeper Friendships

The degree to which we enjoy and derive satisfaction from our relationships will determine our physical health, life satisfaction and subjective well-being.[xli]

It is not the quantity but the quality of the relationship that is important. Quality is linked to the psychological need to belong.[xlii] Brooks and Winfrey in their book, “Build the Life You Want”, assert that “you need at least one close friend besides your spouse [, if you have one,] and there is an upper limit of perhaps 10 friendships that you can realistically spend enough time on to regard them as close.”[xliii]

Brooks and Winfrey also assert that there is a difference between extroverts and introverts in friendships. That is, the former tend to “flit among lots of people whom they know just a little” which can go against them when impacted by the vicissitudes of life and they don’t have anyone in their corner “who knows and loves them deeply.”[xliv] They lack relational connectedness.[xlv] They are bereft of support. Both of which are “linked to desirable emotional, psychological, academic and physical outcomes.”[xlvi] Introverts generally find it harder to make friends but when they do, the nature of their relationships are deeper.[xlvii] As such, they have a greater sense of belonging and relational connectedness.

Extroverts and introverts can learn from each other. The former could seek to have more one-on-one and deeper conversations rather than many surface interactions. Introverts can learn from extroverts and expand more on their hopes and dreams with their close relationships to develop higher levels of happiness and greater likelihood of achieving their goals.[xlviii]

Companionship is a key predictor of happiness.[xlix] Consequently, the quantity and quality of the relationships is important. Brooks and Winfrey refer to “deal” or “expedient friendships” as symbolising the symbiotic relationship that can occur between people who are utilitarian or transactional in nature with each other.[l]These types of relationships are often found in the workplace. These types of relationships lack emotional connection and are what Aristotle deemed lower rung relationships.[li] They serve a purpose but aren’t companionate. Secondly, he suggested there is a relationship based on pleasure – “something you like and admire about other people, such as their intelligence or sense of humour.”[lii] Thirdly, and most importantly are friendships of virtue, of character. These are not transactional but rather “pursued for their own sake.”[liii] It is these types of relationships that promote the greatest life satisfaction and sense of well-being.

Companionate, virtue or character-based relationships are important across the lifespan but especially as we age and the nature of our existence is characterised by changes in meaning, purpose and roles. For example, we may experience a loss of roles be it in the workplace or as a result of loss in personal partnerships as a result of health issues.[liv] Research has shown that it is the quality of relationships with friends that have the greatest impact on morale, life-satisfaction and positive affect and is not limited to psychological well-being but extends to physical and cognitive functioning.[lv] Good friendships are part of ikigai and in addition to quality, frequency of contact with “family, relatives, and friends” is a strong predictor of happiness.[lvi] Failing to stay in touch though is a top five regret of the dying.[lvii]

If you have reflected on your friendships and consider that they are perhaps more “expedient” than “real”, one way to address this is to diversify your source of friendships. Engage in activities and networks that might help you do this but are also real-time as opposed to technological in nature.[lviii]Connecting in “real-time” is an essential ingredient for depth of connection.[lix]

Building deep connections will require time and consistent effort but the rewards are great.[lx] Diversification of roles and support can also be extremely beneficial when we are confronted by challenges and stress.[lxi] They remind us we are multifaceted and, if we’re truly lucky, multi-supported.

6. Be Genuinely Grateful

“Gratitude has been depicted as the willingness to recognise the unearned increments of value in one’s experience and has been discussed and conceptualised as an ‘emotion, an attitude, a moral virtue, a habit, a personality trait [(this, as opposed to state gratitude, tends to be more stable and corresponds with higher well-being and happiness)], or a coping response.’”[lxii]

Gratitude is a positive valued emotion and its emotional underpinning “arises from the perception of a positive, personal outcome” generated from the actions of another,[lxiii] or as “an appreciation for the positive things in life.”[lxiv]

Research has shown that gratitude is positively linked to hope, happiness, indebtedness, life satisfaction, subjective well-being, physical health and positive social relationships.[lxv] The broaden-and-build theory suggests that gratitude promotes expansive thinking which encourages people to engage in behaviour that benefits and enhances others well-being.[lxvi] It ultimately promotes prosocial behaviour.[lxvii] This same theory suggests the positive emotions generated by gratitude also enhances “physical, intellectual, psychological and social reservoirs, enabling people to better cope with life’s many adversities and challenges.”[lxviii]

Underlying the benefit of gratitude is harnessed present centred attention – by focusing on what we feel grateful for, we are focusing on what we have, who has helped us and so forth. We are not dwelling in regret (i.e., focusing on past decisions and negative aspects of the past).[lxix] The shift is positive and is demonstrated with enhanced well-being.[lxx] Garcia and Miralles found that giving thanks daily for all that you are and all that you have (e.g., family, friends, food, fresh air, clean water etc) is also a key component of ikigai.[lxxi]

Where gratitude pertains to family, friends and others, it would be described as a “social emotion robustly related to and foundational in maintaining high quality interpersonal relationships.”[lxxii] Gratitude encourages connectedness and inclusion. The experience of gratitude impels reciprocity thus forming stronger social bonds.[lxxiii] Hence, when we express our gratitude to the benefactor, their perception of us tends to improve resulting in increased closeness[lxxiv] and satisfaction, as research has shown with marital couples.[lxxv] It also assigns the benefactor credit for the outcome which is associated with self-efficacy and elevated levels of self-worth.[lxxvi]

The Find-Remind-and- Bind theory of gratitude suggests that the expression of gratitude to the benefactor enhances the expressor’s perception of the benefactor and the relationship they are grateful for by reminding the expressor of the positive qualities of the benefactor and their relationship with them which in turn strengthens the relationship.[lxxvii] When we don’t say thank you or express our gratitude to the benefactor we miss out on an important potential source of fulfilment as well as an opportunity for personal growth. Saying thank you lets the benefactor know they matter, that we value them and what they have done for us which may in turn facilitate further prosocial behaviour by the benefactor.

Gratitude allows for improved social connection and friendship quality which in turn enhances life satisfaction and well-being.[lxxviii] It is also positively associated with improved physical health, psychosocial traits including a willingness to help others, empathy, forgiveness,[lxxix]decreased problematic functioning, reduced depression and envy and reduced economic impatience and decision making around risk.[lxxx]

Apart from expressing gratitude directly to the benefactor, another means of nurturing the benefits of gratitude and enhancing social closeness is to regularly but not excessively journal about them.[lxxxi] For example, research has found that academic students who regularly engaged with a gratitude journal displayed significant enhancements in academic motivation.[lxxxii]

7. Smile

Humans are social in orientation and social influences are among the influences on brain structure and function that are most powerful in inducing neuroplasticity[lxxxiii].

Research has shown that when we smile, the brain releases endorphins (i.e., these can act as mood elevators), serotonin (i.e., serotonins primary function is to regulate emotional reactions) and dopamine (i.e., this neurotransmitter generally activates other neurotransmitters and aids in pleasure seeking behaviour and thus balances serotonin).

The beneficial effects of smiling are numerous and include[lxxxiv]:

lowered cortisol levels and improved mood which better equips us to manage adversity and challenge as we are better able to problem solve and thus make better choices.

improved memory and learning as the positive mood smiling creates allows the brain to be more receptive to new information.

Increased creativity.

reduced heart rate and blood pressure.

boosted immune system as when we are in a positive mind state, the body generates more white blood cells.

reduced perception of pain and increased pain threshold.

the recipient may smile back.

When we smile, we increase our resilience and well-being, particularly when combined with other positive habits like physical exercise, gratitude and mindfulness practices as discussed above. Adopting a cheerful attitude is not only engaging but has the potential to broaden our social circle and bring us closer to our ikigai.

****************************

References

[i] Garcia, H and Miralles, F (2016). Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life. Penguin. Random House UK pg 56

[ii] Frankl, V.E. (2019). Yes to Life In spite of Everything. Penguin. Random House UK.

[iii] Garcia and Miralles pg 182

[iv] Cited in Dwight, C.K Tsa, Nakamura, J and Csikzentmihalyi, M. (2022). Flow Experiences Across Adulthood: Preliminary Findings on the Continuity Hypothesis. Journal of Happiness Studies. 23:2517-2540

[v] Ibid pg 2518

[vi] Seligman M.E.P. PhD (2011) Flourish. Atria Paperback pg 24.

[vii] Ibid pg 24

[viii] Dwight, C. K Tsa et al (2022) pg 2518

[ix] Ibid pg 2518

[x] Garcia and Miralles pg 70

[xi] Ibid pg 57-58

[xii] Dwight, C. K Tsa et al (2022)

[xiii] Ibid pg 2534

[xiv] Garcia and Miralles pg 86

[xv] Ibid pg 86

[xvi] Ibid pg 96

[xvii] Ibid pg 116

[xviii] Cited in Sekhon, A. (2023) Mindfulness and its Impact on Mental Health: A Review. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology 14 (2), 252-255, pg 253

[xix] Sekhon, A. (2023) p252

[xx] Ibid pg 254

[xxi] Ibid pg 254

[xxii] Ibid pg 252, 253

[xxiii] Garcia and Miralles page 14

[xxiv] Ibid pg 184

[xxvi] Barton, J et al (2012). Exercise-, nature- and socially interactive-based initiatives improve mood and self-esteem in the clinical population. Perspectives in Public Health. Vol 132 No 2. 89 - 96

[xxvii] McCartan, C. PhD, Senior Researcher et al. (2023) Lifts your spirits, lifts your mind: A co produced mixed -methods exploration of the benefits of green and blue spaces for mental wellbeing. Health Expectations. 26:1679–1691

[xxviii] Epel, E PhD (2022). The Seven-Day Stress Prescription. Penguin Life pg 122

[xxix] Barton, J et al (2012).pg 90

[xxx] Epel pg 122

[xxxi] Ibid pg 122

[xxxii] Ibid pg 123

[xxxiii] Ibid pg 123

[xxxiv] Lahart, I et al (2019). The Effects of Green Exercise on Physical and Mental Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1352

[xxxv] Ibid pg 2 of 26

[xxxvi] McCartan, C. PhD, et al. (2023) pg 1680

[xxxvii] Cai, Z.; Gao, D.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, L.; Fang, C. The Flow of Green Exercise, Its Characteristics, Mechanism, and Pattern in Urban Green Space Networks: A Case Study of Nangchang, China. Land 2023, 12, 673

[xxxviii] McCartan, C. (2023) pg 1680

[xxxix] Garcia and Miralles pg 136

[xl] Ibid pg 161

[xli] Song I, Kwon J-W, Jeon SM (2023) The relative importance of friendship to happiness increases with age. PLoS ONE 18(7)

[xlii] Ibid pg 1 of 13

[xliii] Brooks A.C., and Winfrey, O. (2023). Build the Life You Want. Penguin Random House UK.

[xliv] Ibid pg 129

[xlv] Song I, Kwon J-W, Jeon SM (2023) pg 2 of 13

[xlvi] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018). Examining Psychosocial Pathways Underlying Gratitude Interventions: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J Happiness Stud (2018) 19:2421–2444. Pg 2023

[xlvii] Brooks A.C., and Winfrey, O. (2023).pg 129

[xlviii] Ibid pg 130

[xlix] Song I, Kwon J-W, Jeon SM (2023) pg 2 of 13

[l] Brooks A.C., and Winfrey, O. (2023).pg 131

[li] Ibid pg 132, 133

[lii] Ibid pg 132

[liii] Ibid 132

[liv] Song I, Kwon J-W, Jeon SM (2023) pg 2 of 13

[lv] Ibid pg 2 of 13

[lvi] Ibid pg 2 of 13

[lvii] Ware, B. (2011). The Top Five Regrets of the Dying. Hay House Australia Pty Ltd

[lviii] Brooks A.C., and Winfrey, O. (2023) pg 148-150

[lix] Rosen Kellerman, G., and Seligman, M. (2023). Tomorrowmind. Nicholas Breasley Publishing pg 127

[lx] Brooks A.C., and Winfrey, O. (2023) pg 149

[lxi] Epel, E PhD (2022).pg 79

[lxii] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018).pg 2422

[lxiii] Luan M., Zhang Y., and Wang X. (2023) Gratitude Reduces Regret: The Mediating Role of Temporal Focus. Journal of Happiness Studies 24:1–15. Pg 1

[lxiv] Nawa, E. N., and Yamagishi, N. (2024) Distinct associations between gratitude, self-esteem, and optimism with subjective and psychological well-being among Japanese individuals. BMC Psychology 12:130. Pg 3 of 17

[lxv] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018) pg 2422; Luan M., Zhang Y., and Wang X. (2023)

[lxvi] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018).pg 2424

[lxvii] Oguni, R and Ishii, C (2024) Gratitude promotes prosocial behavior even in uncertain situation. Scientific Reports 14:14379

[lxviii] Nawa, N., and Yamagishi, N. (2021) Enhanced academic motivation in university students following a 2-week online gratitude journal intervention. BMC Psychol. 9:71 pg 2 of 16

[lxix] Luan M., Zhang Y., and Wang X. (2023) pg 3

[lxx] Ibid pg 11

[lxxi] Garcia and Miralles pg 185

[lxxii] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018) pg 2423

[lxxiii] Ibid pg 2423

[lxxiv] Ibid pg 2439

[lxxv] Imai, T. (2024) Why do we feel close to a person who expresses gratitude? Exploring mediating roles of perceived warmth, conscientiousness, and agreeableness PsyChJournal.13:79–89. Pg 80

[lxxvi] Ibid pg 85

[lxxvii] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018).pg 2439

[lxxviii] Imai, T. (2024); O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018)

[lxxix] Luan M., Zhang Y., and Wang X. (2023) pg 2

[lxxx] Luan M., Zhang Y., and Wang X. (2023); Nawa, N., and Yamagishi, N. (2021)

[lxxxi] O’Connell, B.H., O’Shea, D., and Gallagher, S., (2018). Nawa, N., and Yamagishi, N. (2021)

[lxxxii] Nawa, N., and Yamagishi, N. (2021)

[lxxxiii] Davidson, R and McEwen B. S. (2012) Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. nature neuroscience volume 15 | number 5: 689 - 695

[lxxxiv] See https://neurolaunch.com/what-does-smiling-do-to-the-brain/